So you thought the last one was tricky to get through? Brother, this one put me into an existential crisis. I’ve actually had this one done for over a year now, so details might be a little less fresh than they otherwise would be. I just needed a break from this stuff after this monster.

So this seems like a simple enough game, yeah? A couple of bi-positional paddles knocking around a ball to hit a few bars, with a score on one side and the number of balls on the other. There are only three player buttons, and heck, we even already worked through some of the kinks regarding digit displays from the last build! We also know so much more about how the video system works, and about TTL gates and design in general.

Well, its one thing to make a simple figure. The playfield, though it did give me a little bit of trouble, is ultimately just ANDing and ORing a bunch of signals together to get what you want. No, the playfield is not the difficult thing to get right here; the small-nation-sized wrench in this project is the ball. Making a single ball bounce around a screen takes a lot of logic-ladder-ing, through use of these little devils called slipping counters, and deciding the direction and speed of the ball by way of a little four-bit code. All of this, of course, is further compounded by the usual errors in the schematic, and this time, even mistakes in the theory of operation!

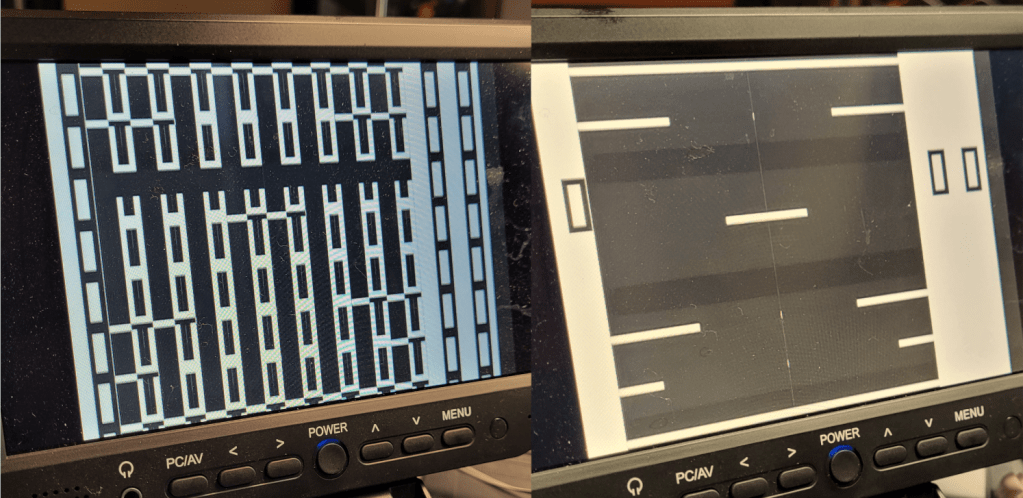

I was kind of lead into a false sense of security for how this was going to go as I discovered some pretty obvious errors at the outset. For instance, here’s my problem/solution pattern I went through with the first few evenings: “Hey, why is the playfield not really showing up? Oh, it’s just some IC sockets you left unsoldered, ya goofball! Huh, still not working quite right… no worries, I’ll just mess around with the graphics logic a bit: invert this signal here, swap these signals around, and boom, now it looks just like in the book! But… where’s the ball?”

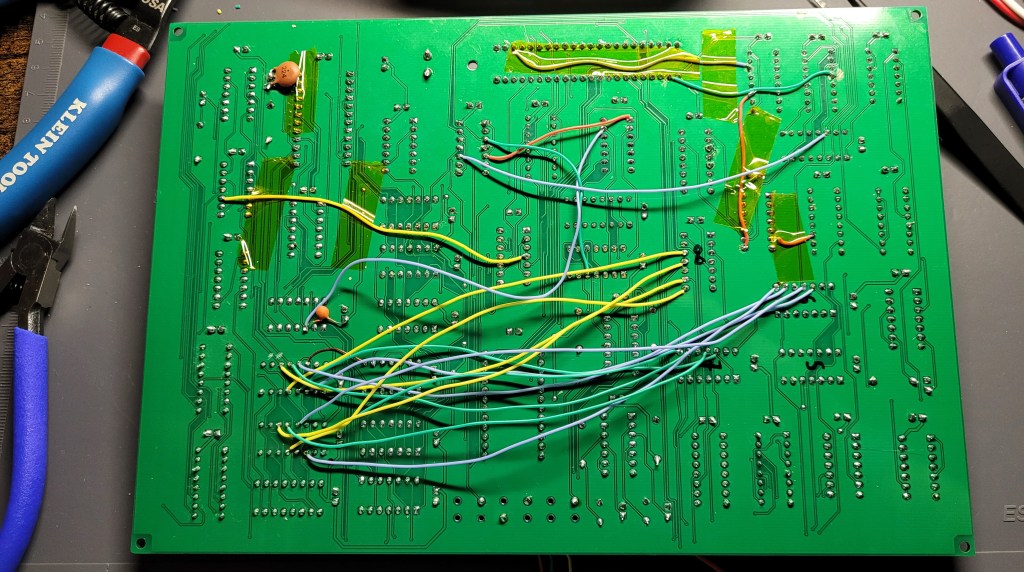

This was, by far, the single most frustrating bug I have ever tried to chase down in these projects. I did manage to get… well, something on screen that at least let me know where the issue lie, which was certainly the slipping counter. Experimenting with some pins a bit (and by “a bit”, I mean probably a dozen hours over several evenings), I was able to get a flurry of dots to cover the screen. And I could somewhat control the volume and velocity of these dots. After several days of signal hunting with my oscilloscope, however, it became clear that the circuit etched onto the PCB was only going to allow me so much experimentation. I had to build up the entire slipping counter circuit on breadboards and bodge the signals into the existing PCB. So I procrastinated for several months.

What makes slipping counters such a pain to diagnose is the fact that they are counters that are deliberately out of sync with the main counters controlling the video signal. It’s a wonderfully simple way to create smooth motion in these early games, but when they’re not working right, their asynchronous nature makes signal mapping an extra chore.

After clearing my head by doing an assortment of other, more therapeutic personal projects, I set to work recreating the slipping counter board on breadboards. It proved not quite as difficult as I had imagined it would be (having quality, BB830 breadboards makes a significant difference), and it appeared simply using the base patterns provided by the video generator would let me know whether or not I was on the right track. This also gave me the opportunity to try different input signals to change the behavior of the circuit. Turns out the horizontal blanking and horizontal clock signals were accidentally reversed in the schematic. Writing this down now, the mistake feels almost trivial; but when you aren’t deeply, DEEPLY familiar with digital logic and analog video, that mistake isn’t going to seem so obvious!

So – a bodge here, a bodge there, and… aw heck, why not send a revised PCB off to the fab for another set of prototypes? We gotta be close, right?

No ball. But angrily pressing the RESET button revealed something… the ball was trying to enter play but kept getting recognizably “bounced” back out of view! I figured it must just be a signal that was misplaced or inverted, and that’s exactly what it was. The !SIDES signal that the ball control circuit needed wasn’t getting pulled from the right spot, another error in the schematic. There was now a ball repeatedly bouncing in between the left portion of the playfield, continually downwards.

I had made it so far. But there was one last major challenge ahead of me. Why does the ball only move downwards?

Poking around with an oscilloscope and playing around with different signals naturally ensued. I was very focused initially on the slipping counter portion of the circuit since that had given me trouble previously, but I quickly reminded myself that I had done a pretty thorough test of that particular circuit with my breadboards, so the culprit was probably found in the ball hit detection and direction circuit. Joy – another complicated circuit with cascading NAND gates. I took a deep breath, and kept repeating the mantra to myself that has continually aided me in these projects: “As long as you learn at least one new thing each evening you mess with it. the experience cannot be considered a failure.”

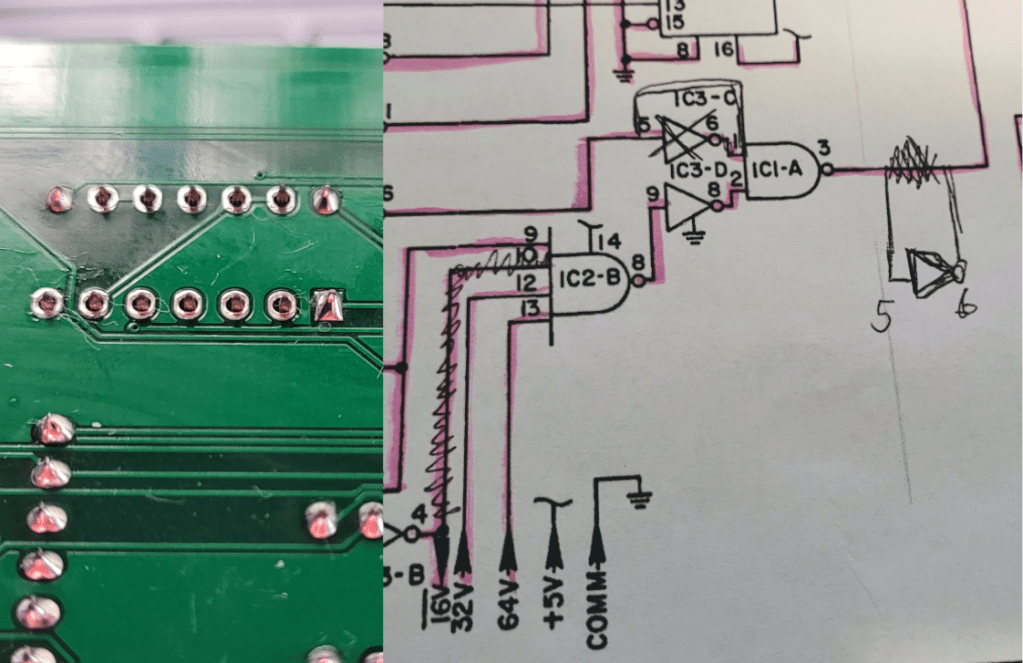

Messing around with signals provided no luck for me here, so I went to the circuit description to see what I could suss out. As I read, my eyes bulged at the carelessness of Tab Books’ editing department. For those who are familiar with digital electronics, see if you can figure out a discrepancy in the text and accompanying schematic…

Down is logic level zero, or low. In order for IC8 to begin the logic to move the ball upwards again, IC4-A has to go low. Now, if you know your NAND gates, you know the only way that will happen is if all the inputs go high. If “down” is always low, THAT’S NEVER GONNA HAPPEN. So a bodge here, a correction to the schematic there aaaaand….

And there we have it. A ball moving bidirectionally on each axis, and a playable game. The score isn’t looking right in this example; that would turn out to be another error in the schematic. The outputs from the score and ball counter going to the score display circuit were backwards. That required the tedious task of cutting traces and soldering bodge wires, but compared to the previous task of just getting the ball to do what it was supposed to, this was a walk in the park. I also made up a quick sound board so it would look more complete. Without further ado, here are the photos of the build itself, the web of bodges on the back of the board, and some footage of gameplay:

It becomes apparent very quickly that there isn’t much to the game, since the ball bounces at the same angle and travels at the same speed, and the paddles can only appear in two different places on the playfield. An immediate idea I had for this game involves having the ball slow down along the x-axis with a left or right “nudge” feature, perhaps also including a timer circuit so that if the ball is nudged too much, it will tilt. I also occasionally toy with the idea of turning the bi-positional paddles into a true, potentiometer controlled pong paddle. But that would require a lot more work than the former idea.

Regardless, getting more or less to a point of success in bringing Heiserman’s design to life reminded me of one of my favorite moments of one of my favorite movies, The Magic Box. It’s a somewhat fictionalized account of English inventor William Friese-Greene’s pioneering work in the development of motion picture film. There’s a scene where, having finally made a working model of his motion picture projector, he manically run downs the street in the wee hours of the morning to find someone, anyone who will share in his ecstasy. He only manages to rope in a suspicious constable (played by Laurence Olivier!) and shows him his achievement. As he hurriedly explains its inner workings, he nearly breaks down, with a glint in his eye, saying:

“I’m not saying it’s perfect; far from it. But it works! God be praised, it works, doesn’t it? You can see that… you know, it’s a quite an extraordinary feeling, something you’ve been wondering about, dreaming about for 15 years, and then – all of a sudden – it’s there! It’s in your hands, with a life of its own.”

I’d like to think that 10-year-old me, mesmerized by this old electronics book he found in the LaGrange Public Library, would be agog to learn that we do actually build the things in that book someday.